Can citizens' assemblies save democracy?

Democracy is declining in different parts of the world, and something must be done about it. Citizens' assemblies create conditions for collective decision-making that both includes and informs the residents – perhaps a way to counter this development?

Despite the fact that many people today experience democracy in crisis, a wave of democratic innovations and exciting initiatives is underway in Europe and the world. Not least in the field that is called deliberative democracy, characterized by a strong focus on the participation of "ordinary people" in the democratic processes through structured and informed discussions. The way of working may feel modern but can be traced all the way back to ancient Greece. As early as 2500 years ago, representatives (officials) were appointed by drawing lots and ordinary (male) citizens were allowed to participate publicly in the political decision-making processes.

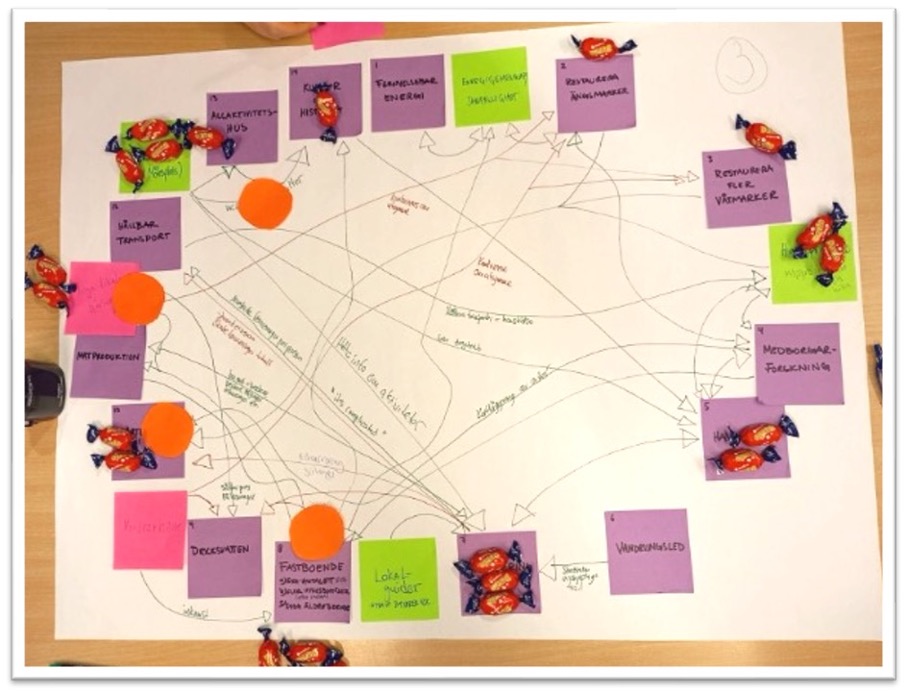

Voxnadalen's citizens' assembly in the autumn of 2024. Residents consulted on how three municipalities best manage their forests in a balance between economic and ecological needs. Author's picture.

Six steps to a citizens' assembly

A democratic innovation that in recent years has aroused increasing interest is what is usually called citizens' assemblies or mini-publics. Through a random selection of participants – who are often stratified into different groups based on demographic or value-based variables – a breadth of opinions is ensured. This avoids a well-known problem in traditional citizens' dialogues, namely that it is the same people or groups who always show up at dialogue meetings. The participants also receive training in the issue to be discussed. With active process management, a constructive conversation is then ensured where everyone can both have their say and listen to others' arguments before reaching decisions or recommendations.

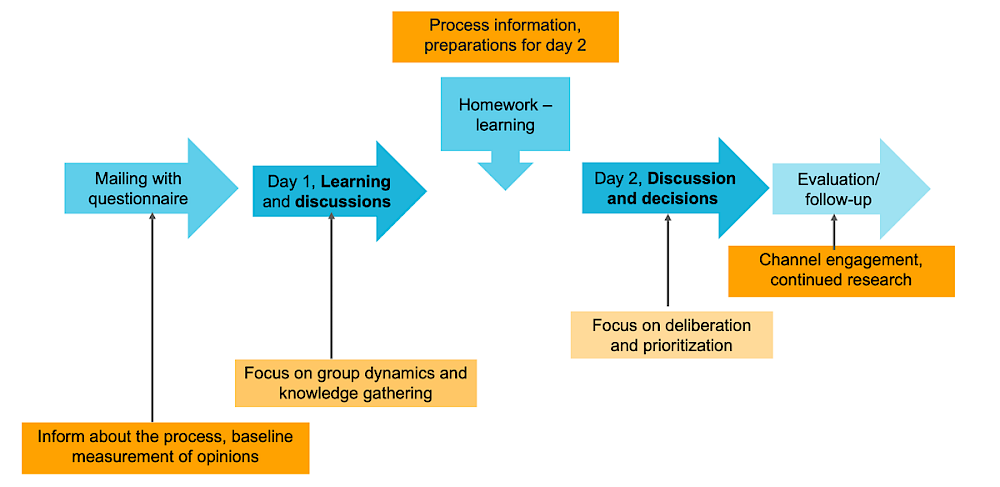

A citizens' assembly is often designed in a number of partly overlapping phases:

- Planning – A qualified steering committee ensures that a fair and inclusive process is developed. Together with the client/recipient, suitable experts/knowledge brokers are also appointed.

- Recruitment Invitations are sent out to a large number of potential participants, often with the goal that the final selection can have a diversity of different perspectives. At the same time, random selection is a key factor. Participation isn’t limited to those who are most engaged and interested. To motivate less committed residents, a small financial compensation is often provided.

- Learning phase – Participants gain knowledge about the topic, often through joint sessions where experts, politicians and other relevant actors present different points of view. Participants can ask questions and can sometimes also serve as experts themselves, especially in local questions.

- Deliberation phase – With the support of impartial facilitators, participants discuss in small groups, reflect on what they have learned, and listen to each other's experiences and arguments.

- Decision-making – Depending on the type of process, the goal of the process can be, for example, recommendations and priorities, decisions, or a measurement of how the participants' opinions have changed.

- Follow-up – To maximize impact, you want to disseminate the results through relevant channels. There is also great potential in channeling the commitment that is often built up in the participants through continued work on the issues.

The design of citizens' assemblies has varied somewhat over time, as the following sections give examples of. However, the basic idea is more relevant than ever, and the development continues, not least through the use of AI. In assemblies with large numbers of participants and lots of created material, today's language models can quickly find patterns and themes. However, it is our conviction that the primary means of democracy are and continue to be meetings and conversations between people.

How are different resources and needs connected? Correlation analysis and sweets as a democratic tool! The local relationship-building that takes place when people receive support to talk about common issues can hardly be overestimated. A bonus in a time of increasing conflicts.

Citizens' assemblies from the 70s onwards

In the 1970s, early attempts were made with what the originator Ned Crosby at the Jefferson Centre called Citizens' Juries. Up to 25 participants were gathered there to discuss an issue for several days. Finally, a joint recommendation was drafted. Other early examples include Planning Cells in Germany in the 70s where many smaller groups discussed the same issues, and Consensus Conferences developed by the Danish Board of Technology in the 80s. Here, too, smaller groups of up to 25 participants gathered.

Towards larger assemblies

During the 90s and 00s, the deliberative processes grew in size. It now became common to have relatively large mini-publics with significantly more participants than before, often close to 100 people or even more who participated in joint deliberations. An interesting example is Deliberative Polling, which was developed at Stanford University. Here, a larger number of participants were first asked to answer questions, as in an opinion poll. Then the participants were asked to learn more about the issues at hand and finally ask the same questions again to see what perceptions ordinary citizens have when they gained deeper knowledge about the issue. Deliberative Polling often has many participants but is carried out over a shorter period of time, typically two to three days.

When ideas for large, often national citizens' assemblies were launched in the early 00s, the scope had grown. The ideal was that at least 100 participants gathered over a large number of days in long processes, sometimes up to a year. For example, constitutional amendments and similar issues have been processed in several countries around the world. However, many citizens' assemblies have not been so extensive, nor are there any fixed definitions of what is required for a deliberative process to be called a citizens' assembly.

When the citizens' assemblies began to make inroads into Sweden a little later, there was not as much focus on the fact that the processes needed to be so large. Sweden also does not have as many inhabitants to be represented. An early citizens' assembly in Sweden was, for example, the National Food Agency's national citizens' assembly, or citizens' panel as they themselves called the process. The focus was on the transition to sustainable food consumption. The panel gathered around 60 people to discuss for four days how it can be possible to eat more sustainably and healthily. The group then submitted its recommendations to the National Food Agency.

The national citizens' assembly on the climate, within the research project FAIRTRANS 2024, is perhaps the most high-profile in Sweden. In a combination of physical and digital meetings, around 60 participants gathered on nine occasions over a period of about three months to listen to experts, deliberate together, and make recommendations.

In addition to these, a number of local citizens' assemblies have been conducted in Sweden, often according to a model where a limited number of participants gather for two or three days. Perhaps a sign that the pendulum has swung back to the smaller extent of the deliberative processes when the movement began.

Citizens' Advice Today and Tomorrow

Kairos Future has recently designed and led two citizens' assembly processes together with researchers and experts from, among others, the Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University. In the Nämdö archipelago outside Stockholm, residents, part-time residents and summer residents gathered to jointly develop priorities and guidelines for the establishment of a so-called biosphere reserve. In Voxnadalen in Hälsingland, citizens from three municipalities met and developed recommendations and priorities for the management of the municipally owned forests.

Both processes were smaller, local citizens' assemblies where the participants gathered for two full days for joint learning, discussions, and priorities. This means a cost-effective process compared to the long and more complex processes that are often required in larger national citizens' assemblies. During the work, we have developed simple methods and models that make it possible for municipalities and other organizations to be able to carry out citizens' assemblies, or why not a member assembly.

Kairos Futures’ model for a simple two-day process. The participants are guided from start to finish.

Finally, the position of democracy in the world today seems to be threatened, and for those who are concerned, there is every reason to seek new forms of inclusion of people. When the wider world is perceived as increasingly chaotic, people's participation in local decision-making contributes to feelings of agency and belonging. We at Kairos Future want to continue to help people and organizations understand and shape the future, and citizens' assemblies are one of many tools for that.

If you want to know more about how you can involve residents or members in deliberative democracy processes, feel free to have a conversation with me.