Migration towards 2030 – Living with the new normal

We again live in an era of great migrations, old borders defied by people and capital looking for new opportunities. Regardless of our feelings toward it, we can be certain that migration will be a major force shaping the world for the foreseeable future – both within and between nations. Migration has always been of great consequence both for migrants and their new neighbors, and Sweden's role here is changing from what's been the case through history – from having a migrant origin we've become a destination. Yet, in the digitally connected global village conditions are very different from what Karl-Oskar and Kristina experienced when they left Ljuder parish for Karlshamn to board a ship to the new world. What impact does this new reality have on your organization?

Sweden has always been a small country tucked away in an inconvenient location at the edge of Europe, dependent on outside influences ever since the viking first ventured east. Immigration from Wallonia in the 17th century made Sweden an iron-working juggernaut, but it's not only through new skills and ideas that immigration can bring wealth. Increasing population is directly linked to increasing GDP and time has shown that more people tend to lead to a more dynamic economy and higher growth. At the same time, immigration is disruptive and disruption can be upsetting. New and disruptive influences are not just opportunities but may well be threats against existing institutions like national cultures or economic safety net systems. Global competition already gives us a tougher, more polarized job market were solidarity is a lot harder to ensure no matter how much it's pushed, and "competition with the rest of the world" is happening no matter what. So, what consequences will the new age of migration have for Sweden?

Migrations will continue

Nothing suggests that migration will stop anytime in the next few decades. The numbers have been going up for a long time and there's no sign this is about to change. The high pressure on Europe right now is due to armed conflict in and around Syria, but even if that tragedy comes to a close other forces driving migration will remain; the demographic transition and the consequences and climate change are likely to lead to keep migration high in the future. The UN predicts that 40 percent of world population will face water shortage by 2050, all while 250 million climate refugees are on the move.

For Sweden, the outlook is clear: to expect population growth. Our relatively high fertility coupled with a steady stream of migrants suggests we will have over 11 million inhabitants by the early '20s (despite having yet to reach 10), according to public statistical forecasts. We've never had such a quick rise before. It will have consequences, of course, for our country and its people. Above all, it will have consequences for the job market and the housing situation - meaning it will affect the whole economy and the welfare state. It will also have a profound effect on the social fabric.

Will you be profitable when you grow up?

A lot of public debate about immigration lately has been about its consequences for Sweden's economy and public finances. But the issue is complex and getting a fair and clear picture of what really happens is easier said than done. It doesn't help that the issue is politically infected and with a strong emotional valence; public discourse is rife with biased narratives, spin and cherry picking in support of wildly diverging agendas. Overall, one thing that researchers can agree on is that getting a foot in the door job market-wise is essential for newcomers. Getting into the workforce quickly makes you a net asset for the economy virtually immediately, unlike homegrown workers for whom it takes 20 years and about 3.5 million SEK (according to SKL) to become employable adults. This means that most migrants, being young adults, can be a great boon for society as long as they can find employment since they have cost essentially nothing when they arrive. However, unemployment is higher for all immigrants, regardless of origin, so unless it gets a lot easier for immigrants to find work here there will be a risk of costs piling up. So getting immigrants into work is the major challenge; if it happens too slowly things will get expensive. Unfortunately it's not looking too good, if we go by the results of the last few years. In 2014 it took a full eight years before the average immigrant had a real job. How can this process be made to work more smoothly? Researchers seem to agree: the keys are language, education and mobility.

But the problem is not just that the skills new immigrants possess and the skills employers need are mismatched, but also that the job market is changing for other reasons. Automation and digitalization is all but certain to lead to a bifurcated economy where some can reach unprecedented highs of productivity while others struggle to compete; the simple yet decent jobs of the golden age of western industrial are history. The jobs of the future will require lots of education and creative/conceptual thought, or be based broadly on relationship management. For both of these job categories, communication and language skills are essential. Today the difference in employment between adults born in Sweden and elsewhere is 15 percentage points, closing that would mean an economic bump worth about 1.5-2 percent of GDP. Migration researcher Joakim Ruist suggests that immigrants' workforce participation would need to increase by 10 percentage points while the retirement age gets raised by a year or two in order to get things on the right track. Over the next few years, while integration effort continues, migration and its effects are projected to account for 8-10 percent of government expenditures. That is a lot and it will put stress on Sweden's public finances and generous welfare state (many municipalities already have to work very hard to integrate both adult refugees and school-age children), but can't be considered a threat to its existence.

Countryside respite

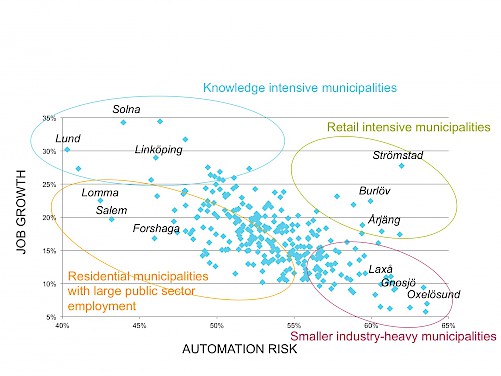

All over the world, migrants aim for large cities. Much of the growth seen lately in the largest Swedish cities is due to migration, as people move to where their former countrymen now live and opportunities are the greatest. This preference for the urban is certain to make the housing situation in Sweden's largest cities even worse than today, especially for the less well off. Despite this, recent inflows of migrants has meant that even municipalities that lose a lot of population to intranational migration has been able to make up the losses by receiving a lot of new people from abroad. In fact, it's municipalities far away from the biggest population centers that have received the most refugees per capita. Many of these are former industrial towns that have been struggling to hold on to employment opportunities and social services. It won't work in the long run though. Unless they can find a way to conjure new job opportunities the new population are just as likely to look to the cities as the natives were. The spectre of automation also hangs over these towns more than others, as they are often dependent on one or a few employers in industries prone to automation. Thus, they risk losing most of the opportunities they do have, making it unlikely that newcomers will stay more than a few years.

Picture: Automation and digitalization will affect different municipalities and their local job markets in different ways over the next decade. Municipalities that receive a lot of refugees are also low on new jobs. In addition, they tend to be more vulnerable to automation eating into the existing jobs. Kairos Future, 2015.

"In Sweden we shake people's hands"

It tends to take three generations before immigrants fully feel at home in their new country. First generation immigrants often feel like visitors even when many years have passed while their children wrestle with the inner conflict a dual identity might bring while trying to enjoy its benefits. Many of these second generation immigrants are driven by a great desire to succeed and make their parents proud; the most strongly driven are typically children of well-educated parents, according to researchers at Botkyrka Multicultural Center.

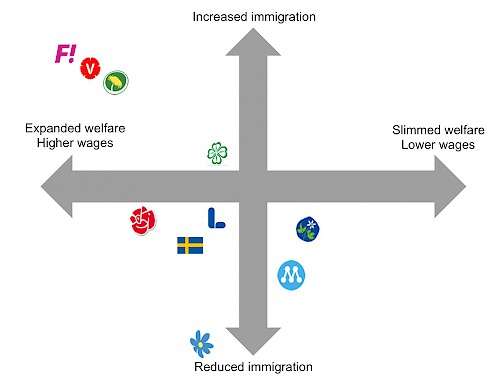

Since over 20 years a majority of Swedes support accepting fewer immigrants but being generous and supportive towards those who do come. That being said, there are significant differences in attitudes towards immigration within the Swedish population, perhaps expressing a fundamental disagreement over what swedishness entails. This schism is mirrored in party politics. The graph below shows how the relationship between immigration and the structure of the Swedish welfare state is viewed differently by supporters of different political parties, particularly with regards to desired future development.

Picture: Swedish people's views on immigration and the future of the welfare system.

Where are we heading? Four scenarios for 2030

The critical factor for determining the long-term consequences of the migration boom is the future of the job market. It underlies the economy, government finances, housing development budgets and ultimately, social order. We've made four simple sketches describing some possible futures. They represent four different paths Sweden can take in responding to increased immigration.

StagNation

Despite automation, intensified international competition and high public costs following large immigration, Sweden has kept its generous welfare state and the Swedish Model. This means that Sweden's job market in 2030 is similar to the one in 2016, insofar that we focus on making people employable by boosting their skill levels. This has not worked for everyone and a large part of the population remains shut out from the workforce. There is also a great willingness to support people living in difficult conditions and that immigration has had significant monetary costs is generally accepted. Many new arrivals found their way into the public sector, ameliorating the shortage of care workers. The shadow economy remains large, even though cash has become almost obsolete, and many newcomers work outside the system. Overall, 2030 is similar to 2016, despite significant changes in technology and lifestyle.

Via Americana

Sweden chose the American path. In the wake of job market deregulation wages drop across the board for all but the high-skill jobs, a necessary action to counter automation and global competition. Being employed at all is considered more important than having high wages, and while this meant the destruction of the traditional labor movement it is generally considered to have been necessary to keep the country afloat. The changes have cut the country in two where the underclass live in poverty, enjoying worse outcomes and fewer opportunities. Disease and disability are more common, housing standards are lower (relaxing building codes have allowed for cheap housing of lower quality than what was possible before) and holiday trips are scant. Weakening the social safety net has meant that it takes on the character on an insurance system, which allows many immigrants to slip through the cracks. They may be employed, but don't enjoy the same level of protection as before. The situation makes a significant fraction of migrant return to their former homes, since the difference in quality of life may not justify staying in Sweden in face if difficulties.

Powder Keg

After a number of job market reforms leading to weaker job security and lower wages for low-skill jobs, dissatisfaction and radicalism start to fester throughout society. Socioeconomic and cultural segregation has kept growing through the '20s, making society less stable. When a global economic crisis hit in '28 a large part of the middle class lost their jobs, and now the disenfranchised make up such a large part of the country that real social collapse seems possible. The precariat is ready to take to the streets and let things blow up in the faces of the comfortable upper middle class. Ethnicity and identity are fault lines in the new conflicts and many of the most impassioned activists trace their ancestry to faraway places. They're fed up with living in a society where the deck is stacked against them by a privileged ruling class of ethnic Swedes trying to maintain the status quo. Many recent immigrants decide to stay in the country despite the difficult conditions, in the hope that a new social order might be coming.

Multicultural Welfare State

When the old social support systems failed to deliver, more and more Swedes chose to take matters into their own hands. Immigrants in particular, often with a tradition of stronger familial bonds and mutual social obligations, turned to non-official solutions. This led to an overhaul of the Swedish social welfare system which changed to embrace that not everyone needs to do things the same way. Some chose to waive certain rights and privileges in order to be more attractive to employers while taking care of protection and support within the family.

The system is referred to as the multicultural welfare state and it means that in Sweden there are different parallel ways to organize social safety nets There is a widespread acceptance for the different systems and the relationship between them characterized by mutual respect. The public authorities and organizations administering taxes and social support have had a tough time adjusting, but the development of sophisticated digital platforms made things go surprisingly smoothly. A disgruntled faction discovered that they were made worse off when some groups decided to opt out of the traditional systems, and they continue to make noise. But for the most part the new compromise is accepted by the Swedish populace - the old and the new one.

Would you like to know more about how to adjust to the new normal? Please contact Erik Herngren. This article is written by Erik Herngren and is based on the report produced for the members of the network Kairos Future Club, read more about membership here.