Future thinking in a transforming economy – A master class in strategic foresight in Zimbabwe

When Kairos Future was invited to lead a foresight master class at the Strategic Intelligence Forum in Harare, Zimbabwe, hosted by the Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries (CZI), the conversation in the room quickly turned from uncertainty to opportunity. Over three intense days of lectures and workshops, industry leaders explored the areas of strategic foresight, AI and sustainability.

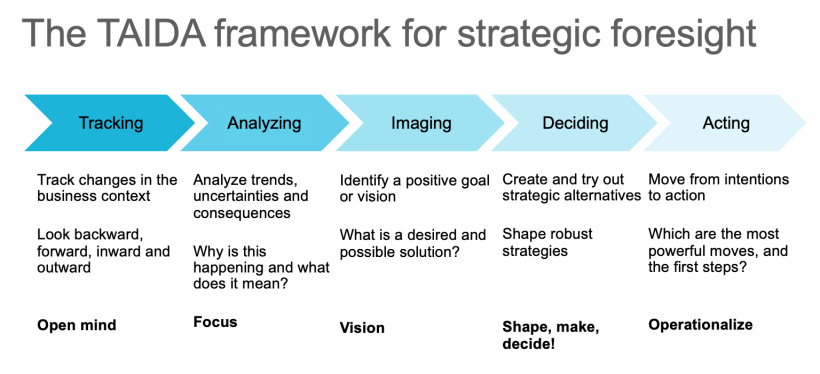

In the foresight master class, we delved into how tools like the TAIDA framework, what-if scenarios, and strategy wind tunneling can help organizations navigate rapid change — anywhere in the world.

In the lobby of the Hyatt Regency Harare “The Meikles”, conference attendees gathered for tea before the start of the conference. Later, in the conference hall, about a hundred executives from Zimbabwe’s leading industries — services, retail, manufacturing, energy, telecom — gathered around tables to discuss one question: How do we build resilient strategies in a volatile and uncertain business landscape?

Over the following hours, we worked through a master class in strategic foresight — a condensed version of the approach we at Kaitos Future Academy teach in the International Certified Future Strategist (ICFS) programme. What unfolded became more than a training session for the industry leaders. It became a conversation full of insights to bring home. Insights about how foresight feels — when the future is not a distant abstraction, but a daily urgency.

A snapshot of the stakes at hand

Zimbabwe’s business environment is full of both challenges and opportunities. Political and regulatory changes can come quickly, sometimes from one week to the next, affecting trade rules, import licences and taxes. Inflation has been high for years, and the value of the local currency changes so rapidly that many companies work with several currencies at the same time — US dollars, Zimbabwean dollars, and even South African rand — just to keep business running. Access to loans and investment capital is limited, and the unstable exchange rate makes it hard to plan prices and investments over time.

At the same time, this has created strong and creative leaders. Many are used to adapting fast, finding new ways to work when conditions shift, and building informal systems to stay resilient. In such an environment, thinking long term is not a luxury — it is a necessity. That is why foresight tools like the TAIDA framework make immediate sense here. They give structure to what many leaders already do instinctively: think ahead, stay flexible, and prepare for change.

In our discussions in Harare, one clear insight emerged: no matter where in the world you work, the hardest part of strategy is keeping direction when the rules of the game may change tomorrow.

Inside the Master class

The master class started with a short lecture about what foresight really is — not about predicting the future, but preparing for it. I spoke about the work of a foresight practitioner, and how the TAIDA framework helps organizations move from observing change to acting on it. TAIDA stands for Tracking, Analyzing, Imaging, Deciding and Acting — a simple but powerful process for making sense of uncertainty.

After this introduction, we moved into a four-part workshop designed to make the concepts practical. The first step was to surface assumptions. Each participant was asked to describe where they expected their business to be in 2030 if they simply continued along their current plans. It quickly became clear how many hidden assumptions were built into these views.

In the second step, we made a quick uncertainty assessment. The group received a list of seven major uncertainties, chosen from a Zimbabwean perspective:

- Economic and financial developments

- Demographics and workforce

- Natural resources and energy

- Agriculture and food security

- Governance, institutions and international relations

- Climate and environment

- Technology and digital transformation

Each team then selected two or three of these that they felt were most critical for their business.

The third step was to polarize these uncertainties — to stretch them to their extremes — and from that, develop “what if” questions for each possible future. What if technology leapfrogged infrastructure? What if access to foreign currency collapsed? What if climate shocks hit food security even harder? The discussions became vivid and concrete, with participants linking possible futures directly to their own operations.

Finally, in the fourth step, we asked the teams to test their current strategies against the different scenarios. This wind-tunneling exercise showed which strategies could stand firm across several futures — and which ones would need adaptation. It was a short session, but the learning was clear: even simple foresight exercises can open the mind to new possibilities and strengthen long-term thinking.

Insights & Reflections

It is hard to convey the experience of these days in Harare, together with these business leaders and the team from CZI. There were an openness and curiosity rare in the West, and a level of strategic thinking and professionalism that impressed me. But what struck me most was the optimism. Despite daily volatility, participants having just learned about these tools seemed to view foresight not as luxury, but as necessity. In environments of scarcity, imagination becomes an asset.

Their questions reminded me that strategic foresight is both global and deeply local. The TAIDA process works anywhere — but the dialogue it sparks depends on culture, history, and hope. For me, it was also a reminder that foresight training is not only about methods, but about mindset — the courage to think long-term when everything around you demands short-term reaction.

Conclusion: Making the Future Happen

The answer to the question posed at the start of this article: Are we victims to the changes coming towards our organizations, or can we use foresight frameworks and a systematic approach to environmental scanning and analysis, in the case of the industry leaders in Zim seems to be distinctively the latter. No matter where we work, the future begins with conversation. In Harare, those conversations were vivid, urgent, and full of possibility — a reminder that the language of foresight truly has no borders.

About the ICFS

The ICFS program builds exactly this kind of future literacy — enabling leaders to move from awareness to action. When I presented the program in Harare, many recognized the same needs within their own organizations: a structured way to track change, imagine alternatives, and decide with confidence.

In today’s global economy, foresight competence is becoming as critical as financial or digital literacy. The ICFS offers a path to build that capacity systematically — in Sweden, Europe, or anywhere forward-thinking leaders gather.

Curious to learn how to master the TAIDA framework for strategic foresight and future-proof your organization? Learn more about the International Certified Future Strategist (ICFS) programme by registering for our free online webinar on November 12th at 3PM CET (UTC+1):

https://www.kairosfuture.com/academy/events/information-icfs/form/34346

Applications for the 2026 ICFS programme, starting January 29th, are now open. Contact Course Director Nina Al-Ghussein Norrman for more information.