Time to reinvent knowledge work with strategies for productivity and well-being

The future of knowledge work is about technology and people, and how to get them to work together. Clearly, the topic is relevant. The hopes and fears surrounding the ChatGPT breakthrough and the popularity of self-help books for professionals demonstrate that the ideal way of life in knowledge economy organizations is not well-defined. To define it, there is much to be learned from history, as a look back at two of history's greatest knowledge workers shows.

First up is Aristotle. His ideas on nature, man and morality have, with few interruptions, been a reference point from ancient times to the present day. In his search for how a person lives his best life, Aristotle ultimately concludes that deep contemplation is one of the highest virtues and most important characteristics of a good life. For without contemplation, it is difficult to master all other virtues, from craftsmanship to statesmanship. From Aristotle, we take away that the ability to think deeply is central to our ability to live good lives because it is what enables us to live up to our potential.

The other historical knowledge worker is David Hume, widely recognized as one of the most important philosophers of the Enlightenment1. Less well known is that early in his career he burned himself out after a manic period of self-punishment2. He was inspired by Stoic philosophy and attempted to study day and night, suppressing all emotions and physical signs of weakness. As a result, he experienced years of impaired cognitive ability.

Hume complained in several letters that after the burnout he never quite regained his full acuity and had to work at a much more moderate pace. This, it should be noted, was before he wrote the works he was known for. Throughout the rest of his career, Hume found it important to exercise, maintain a healthy diet, and socialize in addition to his work. Apparently, this did not hinder his pioneering knowledge work.

From Aristotle and Hume we can learn that deep thinking, given the right conditions, is central to the ability to create new and useful knowledge with our minds. In many ways, this is not surprising. Knowledge work is about adding value to information using your brain. We get the most capacity out of our brains when they are allowed to think deeply about an issue and are not overloaded by too much stress. Paradoxically, these conditions are not always characteristic of the knowledge economy. The fight against time thieves seems to be a more prominent characteristic. The famous physicist Richard Feynman admitted in an interview that he would spread rumors about himself as an unreliable slacker to get out of anything that didn't have to do with his deep thinking on the problems of physics.

Most knowledge workers cannot, like the famous physicist Feynman, simply ignore administrative tasks and feign rudeness to avoid disruption, but are expected to deliver productivity and quality in an environment full of distractions. The stress this creates has spawned a wealth of ironic online culture about micro-managing bosses, meetings that could have been an email, and strategies for dealing with burnout. The imprint is also visible on the New York Times bestseller list. Author Cal Newport3, who coined terms like "digital minimalism" and "deep work" and is now writing a book on "slow productivity," is in many ways writing for an audience trying to cope with a world of digital distractions.

In addition to concrete strategies for how to better organize a workday, Newport and others have written about how to improve the knowledge worker's work life and how to find metaphors and thought models that help us better understand the present. In a podcast interview, Newport likens the habits of many knowledge workers to athletes who chain smoke. The analogy may seem odd, but it's apt. History is full of athletes who smoked, drank, and didn't get enough sleep4. As our understanding of how to improve performance has grown, results in most sports have skyrocketed. Today, the world is full of knowledge workers who are distracted, eat too much fast food, and neglect their sleep. Is knowledge work waiting for the same quality boost from better habits and work-life structures? Four trends from now to later suggest that many should hope so.

Now: Rising number of sick days and major stress problems after the pandemic

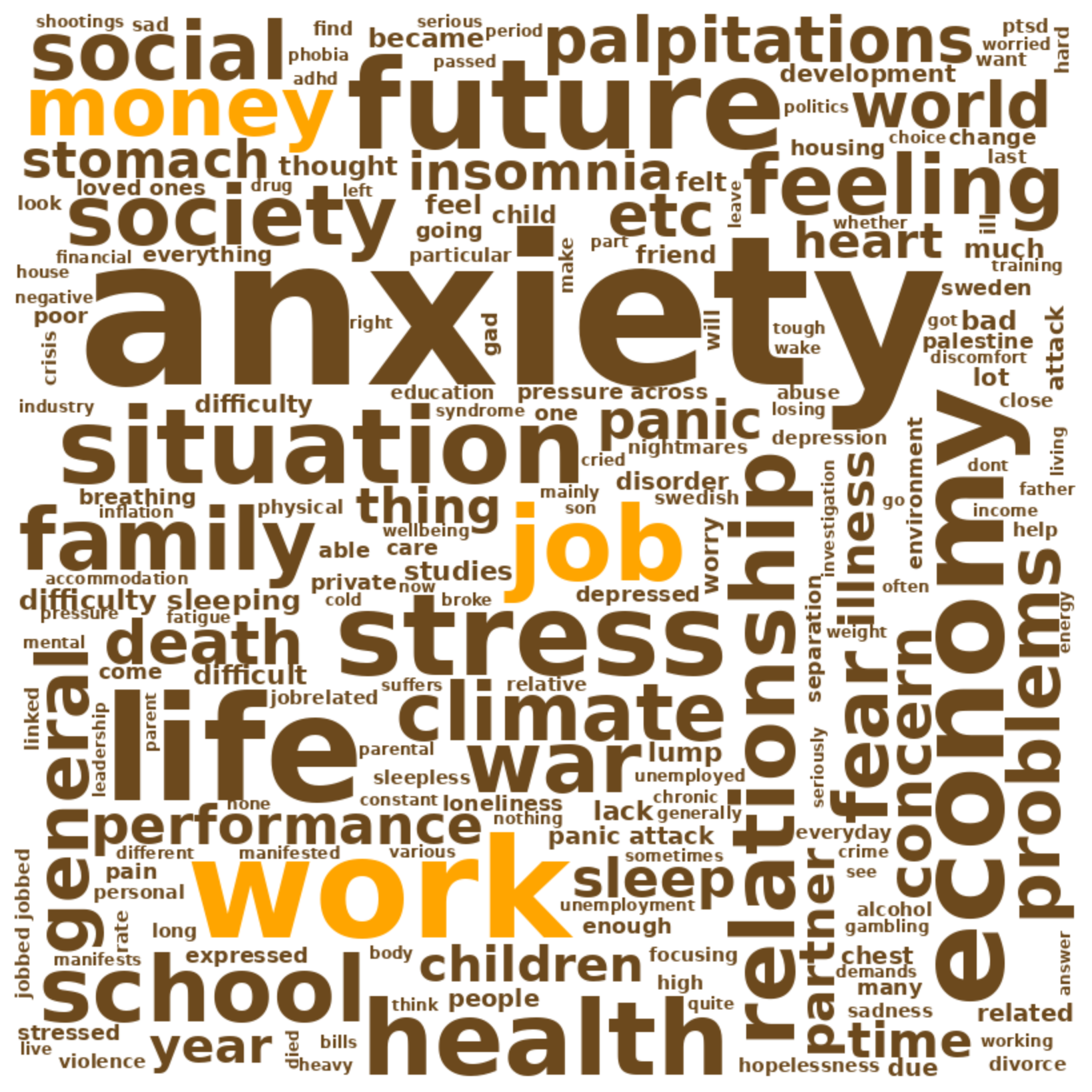

The Swedish Social Insurance Agency reports that a record number of people are on sick leave because of stress-related problems. Mental illness is one of the main causes of long-term sickness. This trend seems to have been exacerbated by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on working life, with increased workloads and constant digital meetings. A Harvard Business Review global survey of knowledge workers during the pandemic found that 89% agreed that their work life had gotten worse5. In Kairos Future's study, Swedes in the Present and the Future, half of all respondents and 75% of 18-29 year olds reported feeling anxious in the past six months. The cause? Work is one of them. Stress-related ill health is costly to individuals and society. But it is also costly in terms of all the deep thinking and innovative solutions we miss out on as a result of burnt-out knowledge workers.

Figure 1: Reasons for anxiety and how it manifested itself

Soon: Generative AI breaks through

Generative AI is now breaking through and impacting knowledge work in ways that are not yet clear. AI has the potential to replace humans in predictable and monotonous tasks with clear "right" and "wrong" answers. It can also be used as a tool to increase the capacity of various types of knowledge work by speeding up tasks, providing editorial support, or acting as a sounding board. So now is the time to think about how AI can support the important thinking that an organization has to do – by creating space for thinking, or by helping to do it. This requires an understanding of how knowledge work is done and the capabilities of knowledge workers themselves. With the ability of generative AI to replace parts of office work that are not knowledge work but more administrative monotonous tasks, the demands on us to learn to use our own brains optimally for deep thinking will increase.

Later: Increased need for innovation and new solutions

A combination of rapid technological developments, economic turmoil, shifting regulations, and changing consumer behavior has created a rapidly changing landscape for businesses, nonprofits, and public organizations, making it harder for them to survive. S&P's list of the 500 largest companies on the stock market shows that their lifespans are getting shorter. Many organizations today are struggling with the need to innovate and find new solutions for everything from their own processes to how they interact with their customers. A Kairos Futures survey6 of European CXOs ranks long-term visionary thinking as one of the most important skills for leaders in the coming years, which aligns well with Alix Partners' findings that 61% of CEOs are concerned about their company's survival.

Making the most of new technologies, seizing opportunities, and, when necessary, reorienting with bold visions and strategies requires innovation. This, in turn, requires well-executed knowledge work. There is thus a link between the work environment and work practices that inhibit effective knowledge work and a lack of innovation. A structural and cultural shift, with more time and opportunity for high quality thinking, may be the medicine many organizations need to successfully address the challenges they face. Such a shift is also in line with what Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky taught with their two systems in the best-selling book "Thinking Fast and Slow"7. The fast System 1 habitually acts according to ingrained thought models. The slower System 2 can change these if given the opportunity to stop and take its time.

Later: Demographic shift cements skills shift

In the longer term, the aging of the population means that each able-bodied person will become more important from a socioeconomic point of view. This is because a smaller number of able-bodied citizens will have to provide for more elderly people while performing in the workplace. For the sake of future economic growth, society simply cannot afford to underutilize the brains devoted to knowledge work8. The social logic also applies at the level of the individual workplace. Demographic change means that fewer able-bodied people are available, which inevitably makes the problem of skills supply more difficult, with increased competition for workers and even greater demands that those recruited actually deliver value to the best of their ability.

The slow productivity advocated by the aforementioned Newport is basically about designing working life so as not to be disturbed and giving the same work area longer periods of uninterrupted focus. The road to this is largely about what we at Kairos Future, in a future analysis together with Avoki9, call digital ergonomics - conditions for doing one's job in a way that does not wear people out, and that enables high productivity. Effective knowledge work in line with Aristotle and Hume, that is, knowledge work with conditions that leave room for deep contemplation and do not burn us out, is an increasingly important strategic issue in both the short and long term. Beyond the purely humanitarian aspect, it is simply in the self-interest of organizations to ensure that human capital has the best conditions to work as well as possible.

[1] Much of Hume's work was, to some extent, about undermining the belief in predetermined causes in nature that sprang from Aristotle's thinking. With his treatises on human nature and the limits of knowledge, he laid important foundations for the structured skepticism and emphasis on empiricism that characterize the scientific method.

[2] See James A. Harris biography of David Hume

[3] https://calnewport.com/writing/

[4] The Tour de France's looting of bars and restaurants is a well-known example

[5] See https://hbr.org/2021/02/beyond-burned-out

[6] Kairos Future & EGN 2023

[7] Daniel Kahneman "Thinking Fast and Slow", Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011

[8] One possible reason why we could be so careless with the brains of knowledge workers could be that there was such a large workforce that it only mattered in some specific cases that everyone really performed at their best.

[9] Se Avokis White Paper om Digital Ergonomi (English) and 5 nycklar till framgång (Swedish)

The text is written with inspiration from our thought leadership report together with Avoki. Interested in how you can maximize your digital ergonomics in times where technology clutter is stealing time and focus? Contact Axel Gruaveus.