The Great Data Chaos (Radical Retail part 5/5)

Over the past five or ten years, data and tech has become the new geopolitical and business battlefield. National as well as corporate competitiveness is increasingly built on the ability to accumulate and capitalize on data, and especially consumer data. But consumers are getting more restrictive in what they share, and thus harder to track. The data war is on.

In the work with Radical Retail Report, a report on retail 2030, produced together with Nexer Group, we identified five shifts that are defining the third retail revolution:

1. Regenerative retail – From Cowboy Economy to Spaceship Economy

2. Phygital experiences – From Transaction Enabler to Experience Provider

3. RADICAL retail – From Manpowered to AI-powered

4. Mytopian retail – From Me in the Marketplace to Me as the Marketplace

5. The Great Data Chaos – From War on Market shares to War on Data shares

This is part 5 of 5 in an article series that outlines the five shifts of the third retail revolution, and presents key take aways for retailers to use in their strategic work towards 2030. References to data can be found in the original report.

Big Numbers in the Data World

We are living in a world of data. A rapidly expanding data world. More than 5 billion people, representing 63% of the global population uses internet every day, up 200 million in 12 months. And almost all of them are active in social media. Internet users conduct 5,7 million Google searches and view 167 million TikTok videos every minute, day in day out. They spend $67k on Instacart, the online grocery platform, and $273k on Amazon, and much more on all other online platforms.

The Internet has taken us from the paradigm of the printing press and broad cast media where information flowed mainly in one direction, to a world where communication happens in network-like messy structures.

All that activity generates data that reveals behaviors, preferences and weaknesses. In total, all the human (and non-human) activity on the Internet generates huge volumes of data. In 2021 there was 80 zettabyte (billons of terabytes) data on the internet, up from five zettabyte ten years earlier. An average new smartphone can store 100 GB, so we are talking storage of 800 billion smartphones.

And this is just the beginning as we are now embedding the physical world with sensors and building digital twins to it. Just take self-driving cars. Every car capture 300 TB per year. If all cars in the world would be self-driving, they alone would generate 450 zettabytes per year, compare that with today’s total internet data of 80 zettabytes.

Big Data – Huge Values

The transition from a world of atoms to a world of data also transforms the world of business. Just a decade ago, the most valuable companies in the world were mostly oil giants and banks. Today they are all tech giants, building their businesses on data, or the tools to manipulate it.

For companies like Google and Meta, it is the user volume that counts, with a market value of on average €100–200 per user. Users generate data that can be used for more precise marketing which make the data giants Google and Meta dominate the world of digital advertising. In Europe, their market share is around 70%, and 99% of Facebook’s revenues in Europe come from advertising.

The Data Power War

Beyond money, data means power. And giving up the data means losing that power. But the data war is complex. For individuals it is a matter of balance between getting relevant content and ads – and giving up privacy. When Safari, Firefox and Chrome implement third-party cookie24 restrictions as default, it is tempting to keep that on. But that also means that the ads will be less relevant, and you need adblockers to get rid of them (which more than 40% already are using).

For other actors, the data war is a war on life and death or long-term prosperity. For example, some websites and retailers can no longer rely on third-party cookies and need to find ways to get first-party consumer data to be able to tailor their services and communication.

For nations, the data war is about protecting privacy, national security and securing long-term competitiveness. That is why the EU has launched numerous initiatives to protect privacy, control tech giants and support European cloud and AI-initiatives to strengthen European industries in the digital field. In a new cold war era, data and tech have also rapidly become the new geopolitical battlefield, where nations for different reasons block providers from competing political spheres.

For companies in the retail sector, the game is about sitting closest to the consumer data, the thick behavior data and the transaction data. Losing that pole position is a big loss, because the data that can be collected there is needed to understand in-depth consumer needs and behaviors, necessary to make relevant tailored offerings to increasingly ad-resistant consumers. Hence it also becomes necessary to secure the right to collect such information, or to be part of ecosystems that have that right. And that requires trust, consumer trust.

A challenge to connecting data to individuals and getting a holistic understanding of a consumer is that young people are increasingly purposefully managing their online profiles. They get several profiles on the same platform, and display only certain sides of themselves on each of them. “Dark Social” is growing, young people have social accounts that are visible to their friends, but not to the general public. This is making it harder for retailers and other actors to identify individuals and target communication. (Jens Nordfält, Professor, University of Bath School of Management).

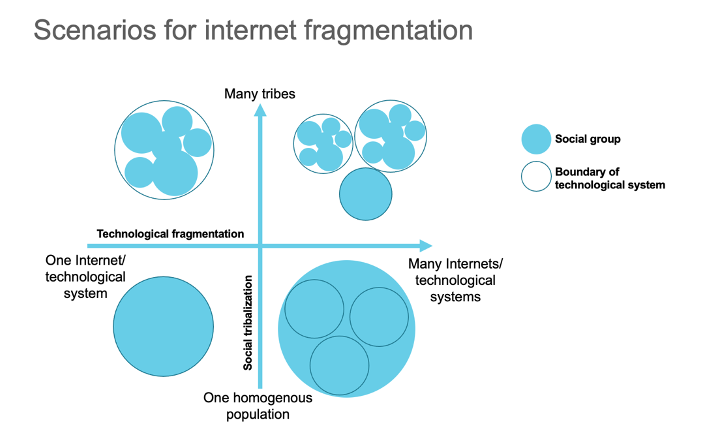

Trends are indicating that we are heading towards the upper right quadrant in the above illustration, with an internet that is increasingly fragmented by technological standards as well as by social groups.

An Open or Closed Future?

One of the key questions forward is whether we are moving towards a more open world, with inter-operability between ecosystems and platforms and across national and regional boarders, or whether platforms will strive for closing their systems, while national security and protectionism will make the world less global.

The endgame is still open. But the tendency today is towards more closed and competing systems, both regionally and platform wise. In the Delphi survey where we asked 150 experts and retail professionals about their views of the future, 65% of those with an opinion predicted internet to be more fragmented geographically in 2030, and 72% believed it to become more divided by technology (blockchains, metaverses etc.). Less than 20% believed in more openness and integration. Although, for instance, the vision of the unified metaverse is strong, it is hard to implement, since it is not only a matter of technical interoperability (which is easy), but also about economic incentives and human behaviors.

Privacy – A Balance Between Privacy, Risk and Innovation

Ownership over and access to personal data is a second key question. On May 25, 2018, the European GDPR regulation came into force. Since then, more than 120 countries around the world have engaged in privacy laws for data protection, including China and India. The reasons are privacy, but sometimes also national security. The latter is the case with the Chinese privacy law from 2021 that was interpreted as not only a crackdown

on the country’s blossoming tech scene but also a recognition of the potential national security risk presented by the mass private collection of data (without setting any boundaries for the government’s data collection).

With more public CCTVs installed, cars packed with cameras and more digital footprints generated, the need for privacy regulation increases dramatically.

But data protection also comes at a cost, especially to smaller companies operating across legislative borders. It also seems to dampen innovation and startup activity. With stricter regulations and higher fines for privacy breaches, the data not only becomes an asset but also a risk. New roles need to be defined, focusing only on data compliance issues, where securing compliance across the supplier and partner network is crucial. Which is burdensome, especially for SMEs, and may also reduce the risk appetite for all companies.

For example, venture capital investment in small and micro companies decreased by $3.4 million per week following GDPR’s enactment due to investor confidence about such companies’ ability to comply. The coming EU regulation around AI, might reinforce these consequences.

Who Will Own the Data in the Future?

If personal information is so valuable, that data aggregators make billions of dollars using and trading it, why shouldn’t individuals own it themselves. That’s the ideas behind the own-my-data movement, such as the Project Liberty, that “aims to create a new civic architecture for the digital world that returns the ownership and control of personal data to individuals”.

At least, we should have control and overview of the data we hare, and easily be able to claim our data back and to be forgotten. The problem is that even that has been complicated. At least until lately when companies like Mine started helping people to take control and delete personal data from services they no longer use with just one click. As an example, 19% of Mine-users have already reclaimed their Amazon data. Is personal control over data a fad or the beginning on a bigger trend? The future will show.

|

|

|

|

|

Theme |

From |

To |

|

Favorable position |

Owning the customer relation |

Owning the consumer data |

|

Data generation |

In ERP systems |

Everywhere, all the time |

|

Type of data |

Small data |

Big and thick data |

|

Retailers’ data usage |

Push and sell |

Engage and serve |

|

Context for supply |

The shop |

The personal feed |

|

Data gathering |

Anything you can get |

Purpose-based |

|

Underpinning technology |

Statistical methods |

Deep learning and transformer models |

|

Data saving |

Everything, forever |

As little as possible, for compliance and cost |

Characterizing sub-shifts for the Great Data Chaos.

Key Takeaways Towards 2030

• The internet will become more fragmented, by geography, technical infrastructure and social grouping. Have you made your scenario planning for the future of the internet?

• Cyber crimes are increasing in numbers and impact. What are you doing to secure your data across all suppliers, platforms and channels at a beneficial risk-level?

• Data collection will become more intentional and purpose- driven, in contrast to the approach “gather all you can”. What is your strategy for capturing and saving a high-quality data set?

• There is a great uncertainty with regards to who will own and have access to consumer data in the future. What is your strategy to get access to the customer data that you need?

This is the last article in the series from the Radical Retail report produced in 2022.